Official records are often treated as the foundation of historical truth. Birth certificates, land deeds, census forms, court documents, and archives shape what societies recognize as real, provable, and legitimate. But across U.S. history, many families have lived with a different reality: records missing, destroyed, misclassified, or never created at all.

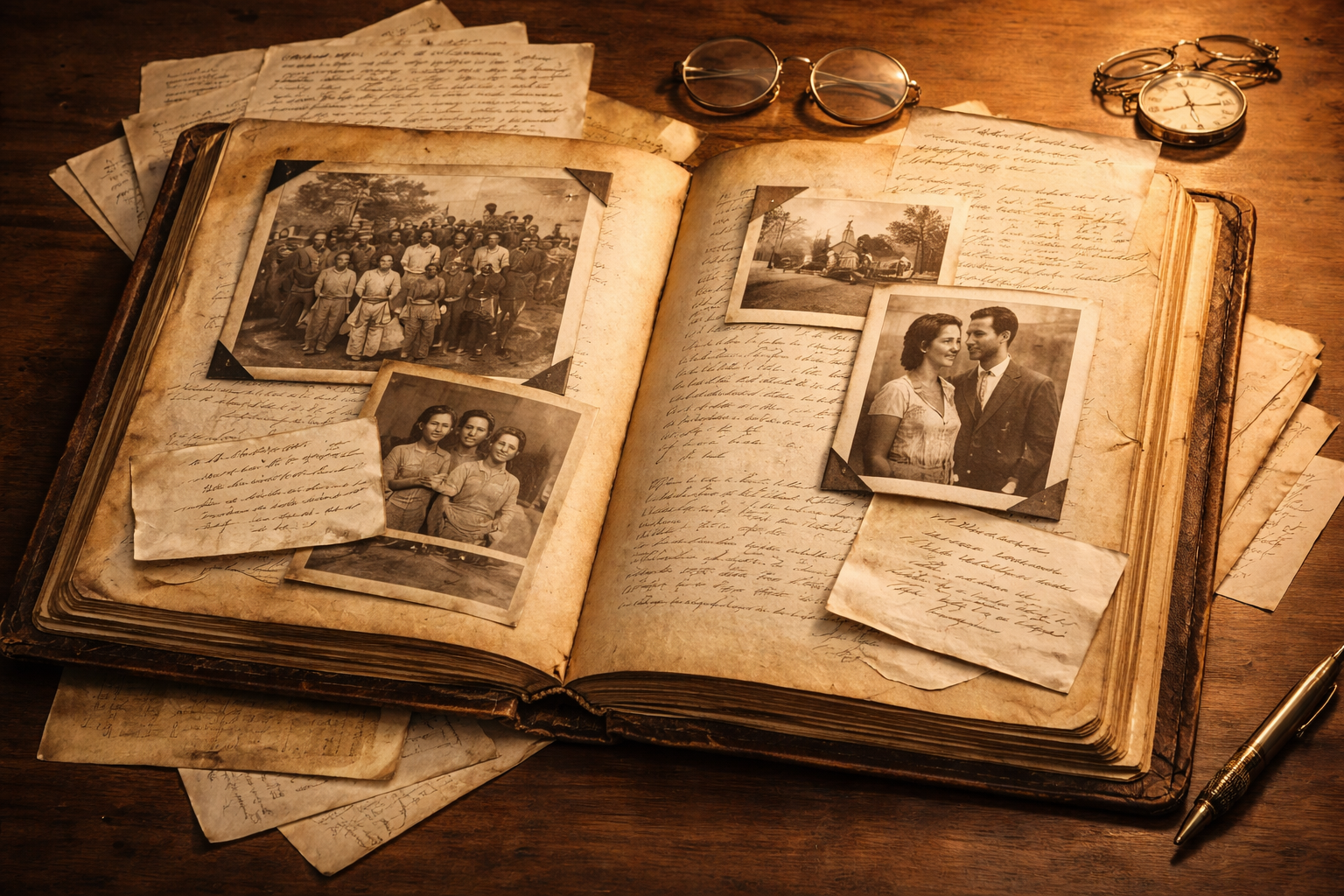

This article reframes family memory not as a substitute for “real” history, but as a parallel system of preservation. When formal records fail—or actively erase—families develop their own methods for carrying truth forward. These practices are not accidental. They are structured responses to historical conditions that made official documentation unreliable, inaccessible, or dangerous.

From slavery through segregation, displacement, migration, and poverty, access to documentation has been uneven.

Enslaved families were routinely separated without written record. Names were changed or omitted. Births, marriages, and deaths were recorded inconsistently or not at all. After emancipation, Black families often relied on oral knowledge to reconstruct kinship because legal recognition lagged lived reality.

Indigenous families experienced similar disruptions. Forced removals, boarding schools, and changing federal classifications fractured records while families maintained lineage, land knowledge, and identity through story, ceremony, and memory.

Immigrant families encountered record loss through migration, language barriers, changing borders, and bureaucratic exclusion. Poor and rural families—across racial lines—often lacked consistent interaction with record-keeping institutions altogether.

In each case, families did not “forget” their histories. They adapted.

Who benefited

Who was harmed

Family preservation of truth emerges in response to recurring structural failures.

Records reflect priorities. Governments document taxation, property, and control more consistently than care, connection, or harm. When families fall outside those priorities, documentation gaps are predictable rather than accidental.

Fires, floods, war, underfunded archives, and intentional destruction have erased vast portions of local and community records. Families often become the only remaining custodians of information once formal systems fail.

Census categories change. Names are altered by clerks, officials, or institutions. Over time, families learn to preserve truth across inconsistent labels—remembering who was who even when the paperwork shifts.

Courts and agencies often privilege written documentation over oral testimony. When families know records are unreliable, they preserve truth internally even when external validation is unavailable.

In some periods, being documented carried danger: exposure to surveillance, taxation, conscription, removal, or violence. Silence in official records was sometimes a protective strategy, while memory remained active within families.

Family-based truth preservation appears across communities, shaped by different pressures.

The common thread is not cultural preference but structural necessity: when systems fail to record truth reliably, families assume the role.

Today, family-held truth continues to surface in genealogy research, oral history projects, community archives, and legal claims. DNA testing, digitization, and crowdsourced records have helped some families reconnect fragments—but these tools often confirm what families already knew.

At the same time, institutional skepticism toward oral history persists. Family knowledge is still frequently treated as anecdotal rather than evidentiary, even when it fills gaps left by documented failure.

Understanding family memory as a legitimate historical system helps explain why some communities resist official narratives: they are not rejecting history, they are protecting it.

When families preserve truth in the absence of records, they are doing more than remembering. They are maintaining continuity, identity, and moral accounting.

Recognizing this challenges the assumption that history flows only from institutions outward. It shows that historical knowledge is often kept alive from the inside, especially by those least served by formal systems.

Acknowledging family preservation of truth expands what counts as evidence, strengthens historical accuracy, and restores credibility to voices long treated as supplemental rather than central.

Library of Congress — Oral History and Family Narratives

https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/oral-history-and-social-history/

National Archives — Genealogy and Family History Research

https://www.archives.gov/research/genealogy

Oral History Association — Principles and Best Practices

https://www.oralhistory.org/principles-and-best-practices/

Amistad Research Center — Family and Community Archives

https://www.amistadresearchcenter.org/

When records fall silent, families often do not. Listening to how truth is carried across generations can change how we understand both the past and the limits of official memory.