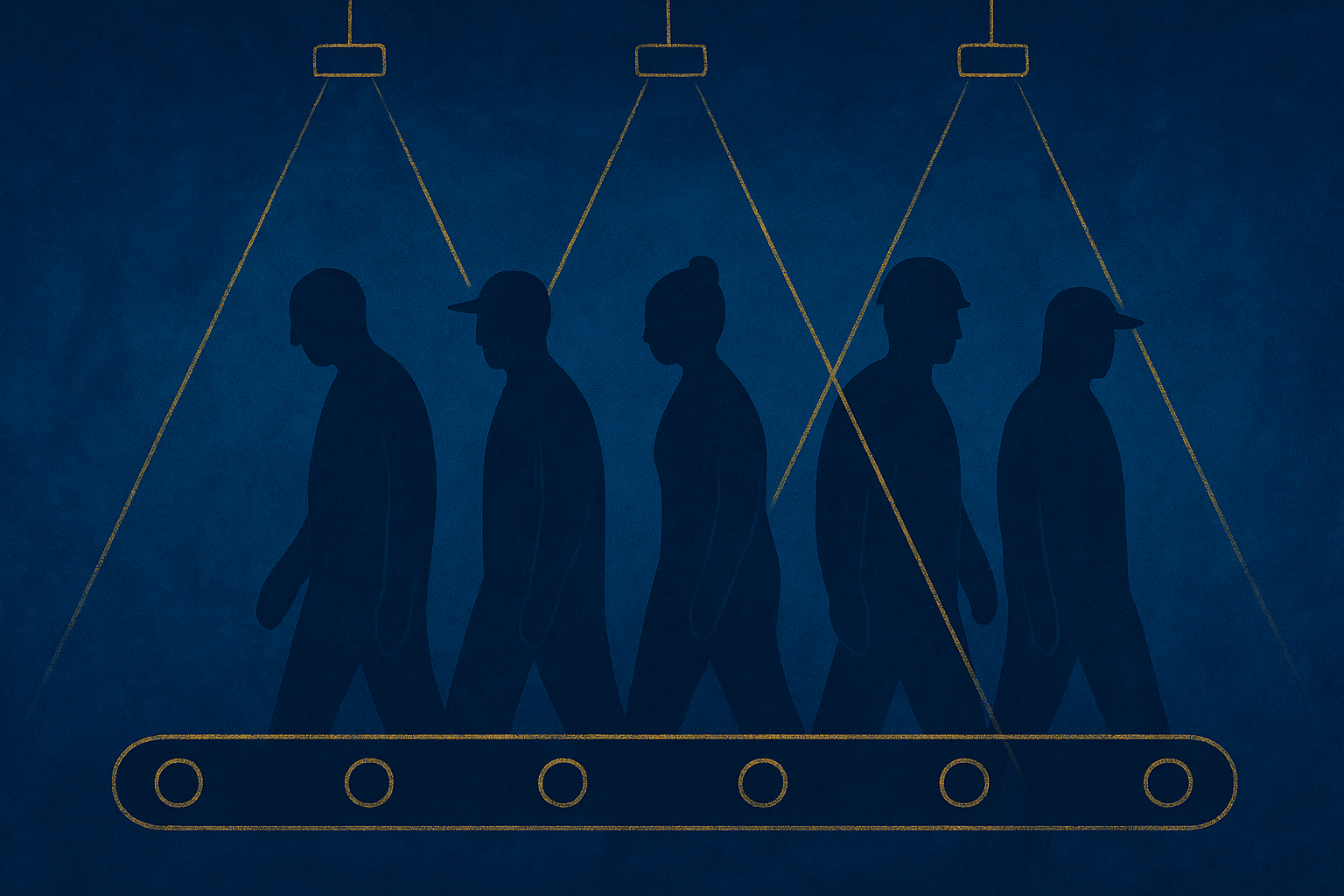

When people talk about productivity today, they usually mean the digital kind — keystroke monitoring, time-tracking software, dashboards, quotas, efficiency scores. But the idea of measuring a worker’s value by numbers didn’t start with computers. It began much earlier, in systems designed to extract labor, rank workers, and control how people spent their time.

Productivity metrics may look modern, but their roots run deep.

To understand why so many workers today feel over-scrutinized, undervalued, or constantly “behind,” you have to look at how American workplaces first learned to measure human output — and whose labor was measured most harshly.

Enslaved people’s work was monitored in exhaustive detail — pounds picked, acres cleared, tasks completed. Enslavers recorded productivity not to value the worker, but to maximize extraction. These records created early templates for labor quotas.

Indigenous children and adults were assigned chores, agricultural output, and industrial tasks, all monitored to enforce discipline and reshape identity.

Railroads, mines, and factory owners set strict benchmarks. Workers from China, Mexico, Ireland, Italy, and Eastern Europe were compared against each other in ways that encouraged competition and justified discriminatory pay.

Black and poor White families in the South were bound to landowners through debts calculated by harvest and labor time, creating one of the earliest systems of quantitative workplace surveillance.

Time spent raising children, cleaning homes, or caring for elders wasn’t recorded or measured at all — reinforcing gender inequality and shaping what society considered “real work.”

Even before industrialization, America had already embraced the idea that labor should be counted, compared, and controlled.

In the early 1900s, engineers used stopwatches and motion studies to measure every movement in factories. Workers became data points.

Tracking shifted from observation to standardized documentation. How long you worked began to matter as much as what you produced.

Companies pitted workers against one another, often across racial and ethnic lines, to drive output.

Surveillance became part of management culture — watching, grading, disciplining.

Black, Indigenous, and immigrant workers often faced harsher monitoring and stricter quotas. Women’s output was measured differently, and often discounted.

By the mid-20th century, America had built a workplace culture where someone was always watching the clock.

Today, many workplaces use:

But the underlying logic is old:

measure the worker instead of the system.

The form changed — the pressure didn’t.

Faced disproportionate discipline and surveillance across workplaces historically, which still shapes how productivity expectations are enforced.

Often subject to lower pay bands and higher quotas, particularly in agriculture, meatpacking, and logistics.

Experienced labor tracking tied to forced assimilation and resource extraction.

Especially in mines, mills, and company towns, productivity systems controlled wages, housing, and debt.

Still face the legacy of unpaid labor not counted in productivity metrics — leading to undervaluation in the workplace.

Algorithmic tracking resurrects many of the same patterns: output measured without context or worker control.

Across groups, the common thread is clear:

productivity systems measure people while ignoring the structures they work within.

When a system values output over well-being, workers across all backgrounds feel the pressure.

Today, workers and advocates are pushing back:

The most meaningful reforms come from listening to the people being measured.

Because it reveals a simple truth:

Metrics don’t just describe work — they shape it.

When the roots of measurement come from unequal systems, the outcomes reflect those inequalities. Understanding this history helps us:

A fair workplace starts by questioning what — and who — we choose to measure.

Library of Congress — Labor and Industry Collections

https://loc.gov/

NIOSH — Workplace Stress & Monitoring History

https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/

National Museum of American History — Work & Technology

https://americanhistory.si.edu/

International Labour Organization — Global Labor Trends

https://ilo.org/