Race feels like something that has always existed, like weather or gravity. But in America, race wasn’t something people discovered — it was something people built. Brick by brick, law by law, year after year, the idea of “race” was constructed to sort people, control people, and justify who got access to what.

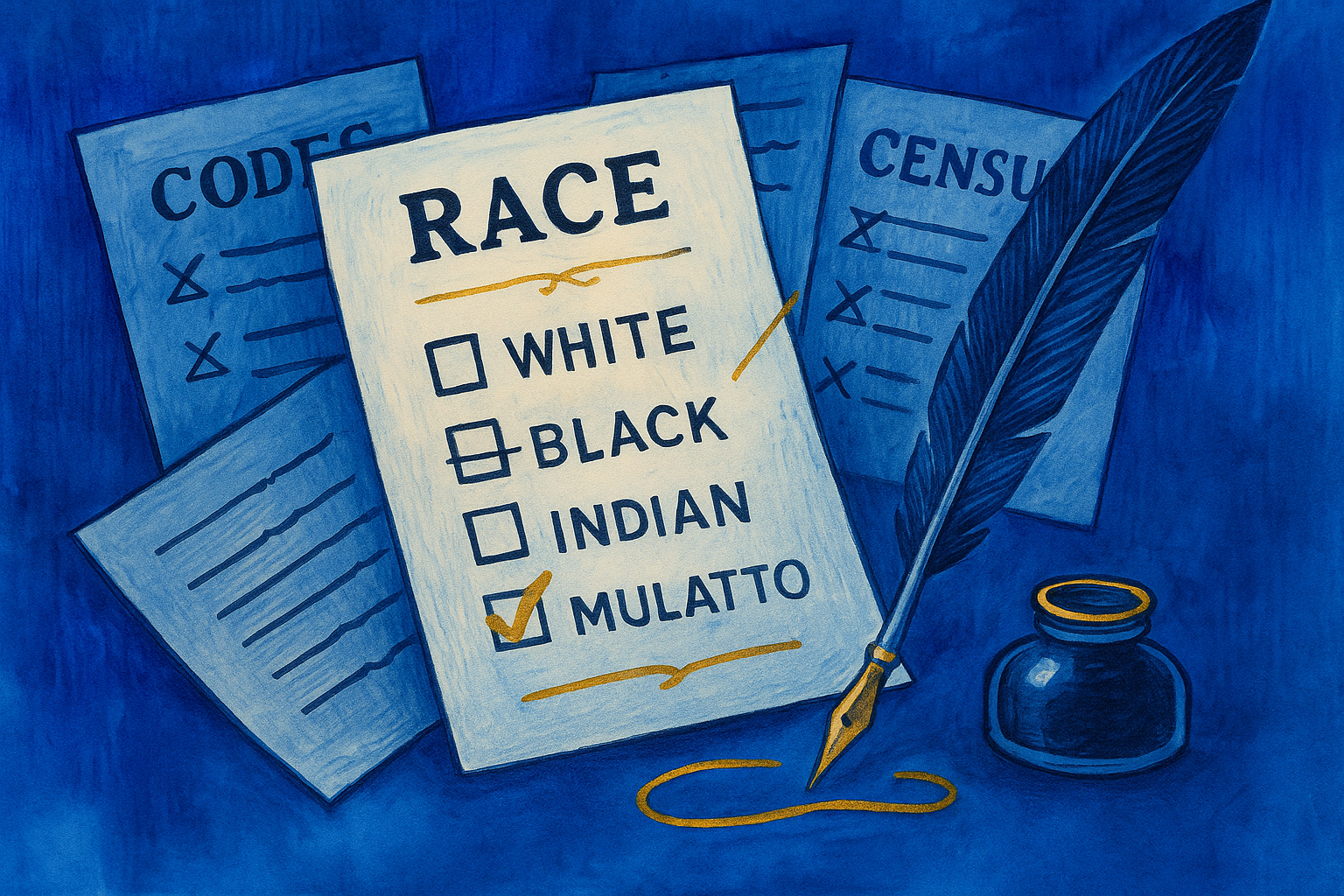

That’s the part most of us were never taught. We grow up hearing about “racial tensions” or “racial divisions” as if they happened on their own. But when you look deeper, you realize that what we call “race” was shaped intentionally through legal codes, court decisions, census categories, and economic incentives. It was a system that didn’t emerge naturally — it was engineered.

And understanding how it was engineered isn’t about dwelling on the past. It’s about seeing clearly how the rules of the game were set up, because those early choices shaped opportunities, neighborhoods, family histories, and even how we understand ourselves today. Once you see how something was built, you can finally understand how to rebuild it better.

In the 1600s, early American colonies were still figuring out how to organize their societies. People came from many places — West Africa, England, Ireland, Indigenous nations, the Caribbean — and early records show far more fluidity than we imagine today. People worked together, lived near each other, and sometimes even formed families across these lines.

But the people in charge had a problem: they needed to stabilize an economy that depended heavily on forced labor. And the biggest threat to that system was unity — the possibility that poor Europeans, free Black people, and enslaved Africans might band together.

So colonial lawmakers got to work. They began creating race as a set of legal categories that determined:

A few examples that reshaped America:

A law in Virginia declared that a child’s status followed the mother. If the mother was enslaved, the child was enslaved. This single law massively increased the economic value of controlling Black women’s bodies.

Colonies banned marriages between Europeans and Africans or Indigenous people. These laws were not about “morality” — they protected a racial hierarchy.

These early codes lumped people into racial categories with different punishments, rights, and legal protections. The line between “white” and “Black” hardened.

The government classified people into constantly shifting racial boxes (“mulatto,” “quadroon,” “octoroon,” “colored”), revealing just how constructed these categories really were.

States like Virginia made the “one-drop rule” legally binding: any known African ancestry classified a person as “Black.” A system of rigid racial boundaries had become law.

By the early 20th century, race wasn’t just an idea — it was an entire legal structure that shaped land ownership, inheritance, citizenship, healthcare, education, and opportunity.

It’s true that Black Americans were most directly targeted by these racial categories — their lives, families, and labor were controlled through them.

But the system reshaped life for many other communities as well:

Separating poor Europeans from enslaved Africans reduced the chance they would unite around shared economic struggles. Racial privilege became a substitute for real economic opportunity — a pattern still seen today.

Racial classification was used to justify land seizure, forced removal, and assimilation policies.

Irish, Italian, Jewish, Mexican, and Eastern European communities were at various points classified as “not fully white,” meaning limited job access, housing restrictions, and discrimination.

Race determined which women were considered “fit” mothers, whose children were valued, and whose bodies could be exploited by employers, the courts, or the state.

Once race became baked into property law, education systems, and public policy, the effects rippled forward for centuries — shaping wealth gaps, neighborhood segregation, and health outcomes.

These structures didn’t just sort people — they changed the entire trajectory of millions of families.

Many modern systems still echo the original legal categories:

When people say “race is real,” they’re right — but not because biology made it real.

Policies made it real. And policy can be changed.

Understanding the construction of race helps communities see:

And here’s the key point:

Systems built on inequality eventually harm everyone, not just the people they targeted first.

Housing discrimination didn’t stay limited to Black neighborhoods.

Predatory lending didn’t stay confined to cities.

Voting restrictions don’t stay targeted at one group.

Underfunded schools weaken entire regions, not just one block.

If the problem was constructed, the solution can be constructed too — together.

Smithsonian – Race: The Power of an Illusion

https://www.racepowerofanillusion.org/

Library of Congress – Early American Legal Codes

https://www.loc.gov/collections/slavery-and-law/

National Archives – Laws Governing Race and Citizenship

https://www.archives.gov/research/alic/reference/legal-history

Equal Justice Initiative – The Legacy of Racial Caste Systems

https://eji.org/reports/segregation-in-america/

Virginia Museum of History – The Racial Integrity Act

https://virginiahistory.org/learn/historical-bookmarks/racial-integrity-act

University of North Carolina – Digital Slavery and Race Collection

https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/