Many modern debates about voting are framed as unprecedented.

New technologies. New concerns. New rules.

But when viewed historically, most contemporary voting restrictions are neither entirely new nor entirely old. They are adaptations—reworked versions of earlier barriers, updated to fit current legal and political conditions.

Understanding what has changed, what has persisted, and what has been repackaged helps clarify why voting access remains contested even after major expansions.

Throughout American history, voting restrictions have followed a pattern.

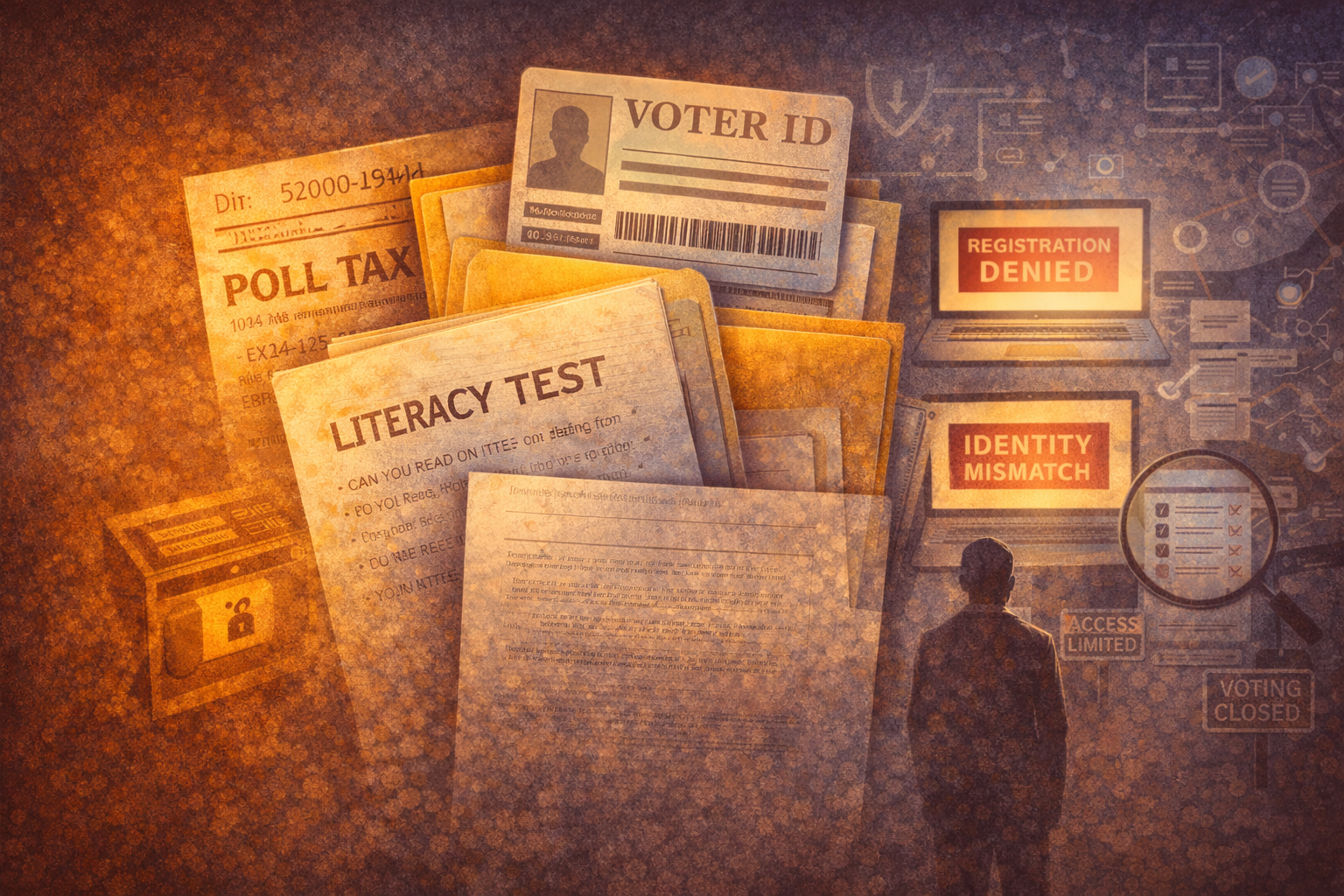

When one method of exclusion becomes legally or politically untenable, another emerges. Literacy tests and poll taxes gave way to administrative hurdles. Explicit racial language gave way to race-neutral framing. Local discretion shifted into procedural complexity.

The goal remained consistent: managing who participates without appearing to deny participation outright.

Modern restrictions operate within this long tradition of adaptation.

Many contemporary voting rules echo earlier strategies.

Requirements tied to documentation, registration timing, residency, and eligibility mirror older systems that relied on literacy, payment, or bureaucratic compliance.

The mechanics differ. The logic is familiar.

Rules that assume flexible schedules, stable housing, reliable transportation, or access to official documents disproportionately affect the same communities that faced earlier forms of restriction.

The language has softened. The structure remains.

Modern systems introduce new elements.

Digital databases, automated purges, algorithmic matching, and centralized voter rolls allow restrictions to operate at greater scale and speed than before. Errors can spread widely before being detected. Corrections often require individual effort.

These systems are often justified as efficiency measures. Their impacts, however, are uneven.

Technology does not remove discretion. It redistributes it.

Perhaps the most significant change is rhetorical.

Modern restrictions are rarely framed as limiting access. They are framed as protecting integrity, preventing fraud, or maintaining public confidence.

These arguments are not inherently illegitimate. But history shows that neutral framing has often accompanied unequal outcomes.

When rules are defended as technical rather than political, their effects become harder to challenge—and easier to normalize.

As in earlier eras, the effects are not evenly distributed.

Black Americans and other racial minorities continue to experience higher rates of registration challenges and ballot rejection.

Low-income voters are more likely to encounter barriers tied to time, transportation, and documentation.

Elderly voters, students, and people with disabilities face hurdles when systems assume uniform access or capacity.

The pattern is consistent: those with the least margin for error bear the highest cost.

Modern voting restrictions cannot be understood in isolation.

They are part of a longer story—one in which exclusion adapts rather than disappears, and where progress triggers recalibration rather than resolution.

Recognizing what is new, what is old, and what has been repackaged allows for clearer evaluation of claims about fairness, necessity, and neutrality.

Democracy is not only shaped by who is allowed to vote, but by how participation is managed.

Modern voter restrictions rarely announce themselves as such.

They arrive as updates, safeguards, or efficiencies—often building on older ideas with new tools.

Every Chapter Counts examines these patterns not to collapse past and present, but to restore context. When we understand how restriction adapts, we gain clearer sight of the systems shaping participation today.