By the mid-twentieth century, voting rights in the United States were guaranteed in law but uneven in reality.

Black Americans technically possessed the right to vote, yet millions were blocked from exercising it through intimidation, administrative barriers, and selective enforcement. Courts addressed individual abuses slowly, one case at a time. States adapted faster than the law could respond.

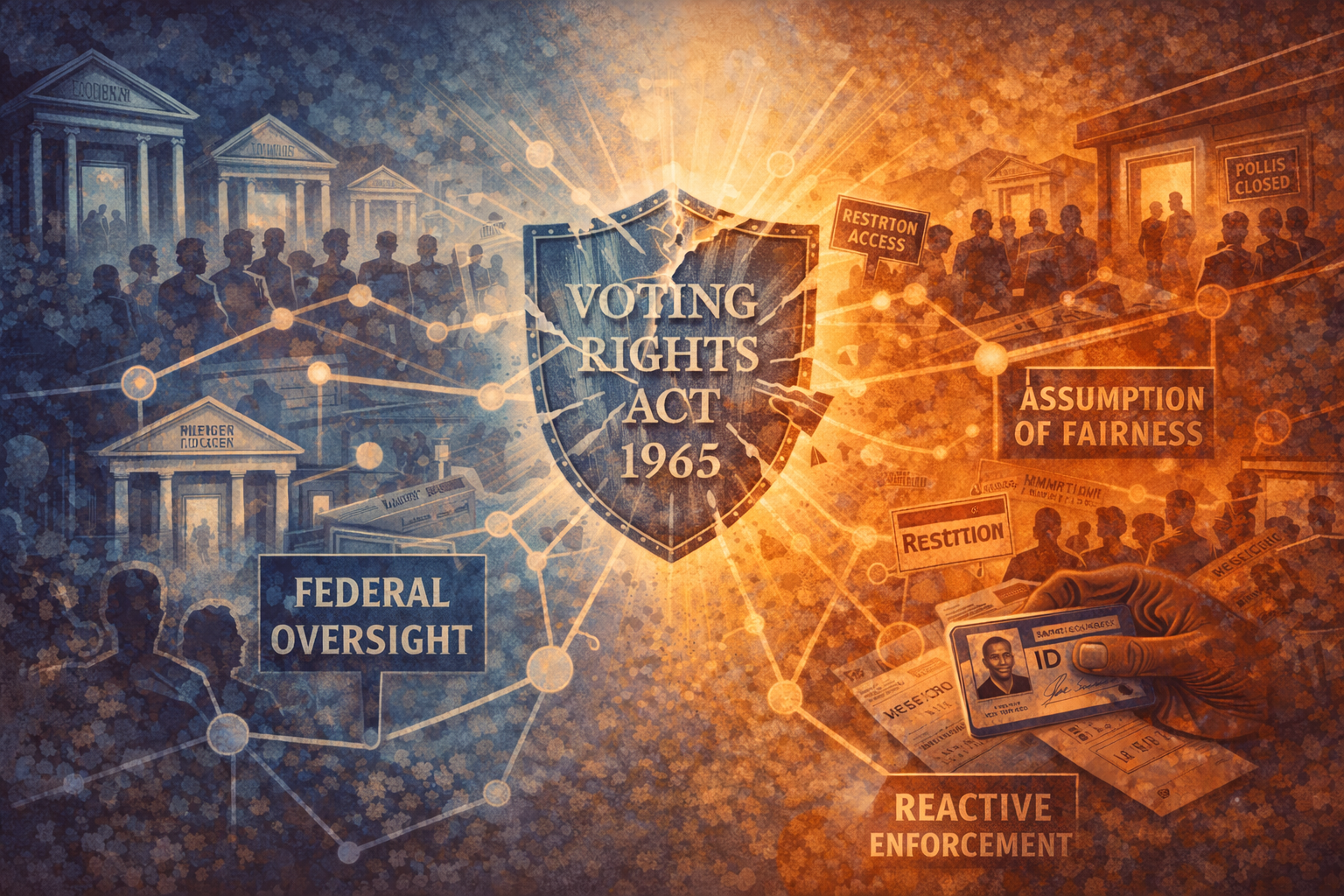

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was created to close that gap—not by promising rights, but by enforcing them.

Understanding why it was needed, and what changed when its protections were weakened, helps explain why voting access remains contested today.

Before 1965, constitutional amendments prohibited racial discrimination in voting. In practice, enforcement relied on litigation.

That approach had limits:

Suppression did not depend on a single rule. It depended on systems—poll taxes, literacy tests, registration hurdles, intimidation, and discretion exercised by local officials.

The Voting Rights Act addressed this reality directly. It recognized that equal access could not be achieved solely through after-the-fact lawsuits.

The Voting Rights Act introduced a different approach.

Rather than requiring voters to prove discrimination after it occurred, the law required certain jurisdictions with histories of suppression to prove in advance that new voting rules would not be discriminatory.

This preclearance requirement shifted the burden:

The results were immediate. Voter registration and participation increased rapidly. Barriers that had persisted for decades were removed in years.

The law did not eliminate conflict. It reduced opportunity for quiet suppression.

The Voting Rights Act most directly benefited Black Americans in the South, where suppression had been most entrenched.

But its effects extended further.

Language minorities gained protections that improved access for immigrant communities.

Low-income voters benefited from simplified registration and oversight.

Rural and marginalized communities experienced more consistent enforcement of voting standards.

The law did not privilege one group. It addressed patterns of harm.

Decades later, the logic of the Voting Rights Act was challenged.

Arguments emerged that the conditions justifying federal oversight no longer existed—that discrimination had declined enough to make preventive safeguards unnecessary.

When key protections were weakened, oversight shifted back toward reactive enforcement.

States regained flexibility to alter voting rules without prior review. Some changes were modest. Others had measurable effects on access.

The system did not return to the past. It entered a new phase—one where restriction could occur without automatic scrutiny.

Without preclearance, challenges to voting laws rely again on litigation.

That means:

The debate is often framed as legal or technical. But the practical question remains the same: who bears the burden when access is restricted?

History suggests that burden is rarely shared equally.

The Voting Rights Act demonstrates that rights are not only defined by principle, but by enforcement.

It shows why prevention matters more than correction in systems with long histories of adaptation. And it explains why weakening safeguards does not require intent to produce unequal outcomes.

Democracy depends not only on formal equality, but on sustained protection.

Voting Rights Act

Legal Context

The Voting Rights Act was not an overreach. It was a response to reality.

It acknowledged that discrimination adapts, that enforcement matters, and that rights require protection to be meaningful.

Every Chapter Counts examines this history not to argue permanence or decline, but to understand why safeguards were built—and what changes when they are removed.