Every nation tells stories about itself.

These stories appear in textbooks, monuments, holidays, speeches, and shared phrases about identity and purpose. Over time, they begin to feel natural—less like narratives and more like facts.

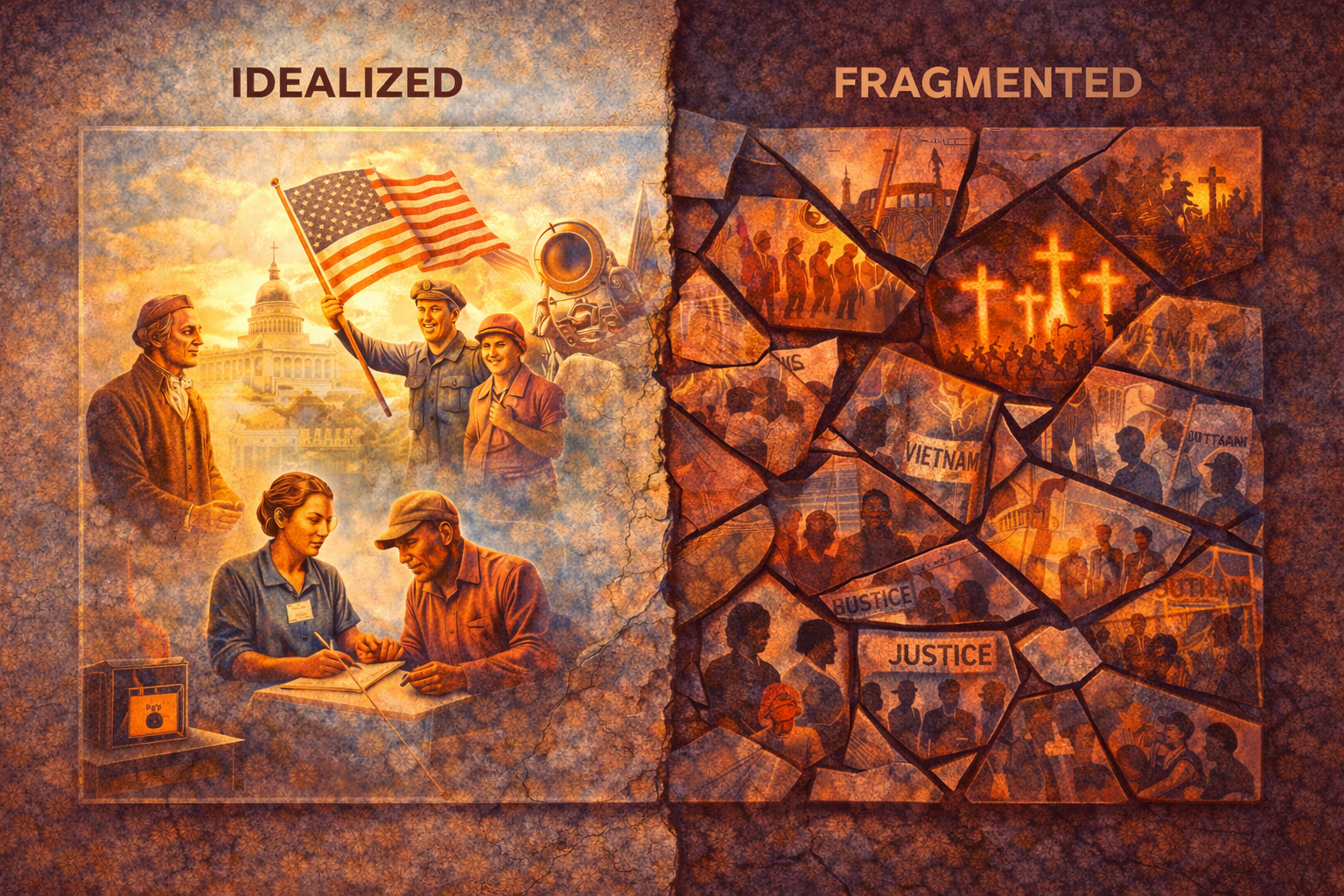

But national memory is not a neutral record of the past. It is shaped by psychology as much as history. What a society remembers, emphasizes, or forgets often reflects emotional needs as much as evidence.

Understanding national mythmaking helps explain why some histories are elevated, others softened, and still others erased.

Collective memory does not form automatically.

It is built through institutions—schools, media, museums, laws, and rituals—that decide which stories are repeated and which are sidelined. These decisions are rarely coordinated, but they tend to align around shared incentives.

Nations, like individuals, seek coherence. Stories that affirm purpose, progress, and moral clarity are easier to sustain than those that introduce contradiction or discomfort.

Over time, repetition becomes belief.

National mythmaking follows recognizable psychological patterns.

First comes selection. Events that support a coherent narrative are highlighted. Others are minimized or omitted.

Next comes simplification. Complex histories are reduced to heroes, villains, turning points, and resolutions.

Finally comes stabilization. Once a narrative is widely accepted, it becomes resistant to challenge. Contradictory information is reframed as marginal, divisive, or unnecessary.

This process does not require conspiracy. It emerges from shared habits of attention.

Certain themes appear repeatedly in national memory:

These memories reinforce identity and belonging. They make the past legible and the present reassuring.

They also set boundaries on what feels “appropriate” to remember.

Other elements tend to recede:

Forgetting does not always mean erasure. More often, it means dilution—events are acknowledged briefly, framed gently, or disconnected from present consequences.

What is forgotten is often what complicates the story.

Mythmaking does not affect all groups equally.

Dominant groups often see their experiences reflected as universal, reinforcing belonging.

Marginalized communities may see their histories compressed, distorted, or omitted—creating a gap between lived memory and national narrative.

Younger generations inherit these narratives before they have tools to question them, shaping baseline assumptions about fairness, progress, and responsibility.

The result is not ignorance, but partial understanding.

National myths do not remain in the past.

They shape how societies interpret present challenges. If a nation believes injustice is an exception rather than a pattern, structural explanations feel excessive. If progress is assumed to be inevitable, regression feels implausible.

Disagreements about policy often reflect deeper disagreements about history—about what counts as normal, resolved, or relevant.

Memory sets the frame before debate begins.

Understanding national mythmaking does not require rejecting shared stories.

It requires recognizing that memory is selective—and that selection has consequences.

When societies revisit what they remember and why, they gain the ability to expand understanding without collapsing identity. Complexity becomes a strength rather than a threat.

Every Chapter Counts approaches history not to replace one myth with another, but to widen the lens of memory itself.

National myths are not lies. They are stories shaped by need, repetition, and emotion.

By examining what we remember and what we forget, we gain a clearer view of how history functions—not just as record, but as framework.

Every Chapter Counts invites readers to engage that framework thoughtfully, expanding memory without losing meaning.