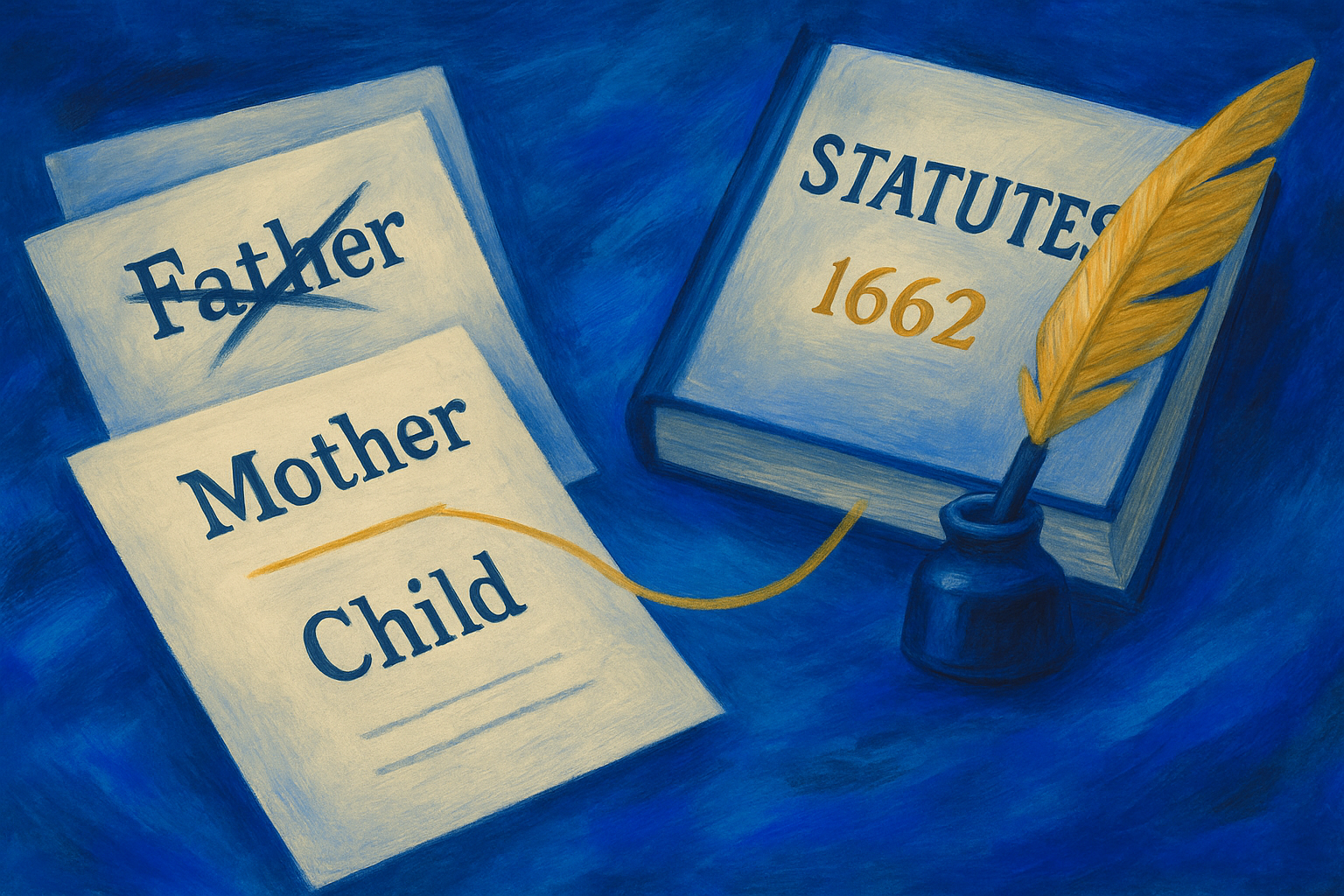

Most of us grow up thinking that family lineage — the idea of who a child “comes from” — is a simple, natural truth. But in early America, lineage wasn’t just a family matter. It became a tool of policy, economy, and power. And one law in particular changed the course of history for millions of families: the 1662 Virginia statute that declared a child’s status followed the mother.

That sounds harmless at first glance, but it flipped centuries of European tradition on its head. Under English common law, a child’s status followed the father. But the colony’s leaders made a strategic decision: they rewrote lineage to serve the growing system of slavery. And that quiet legal shift — just a few lines of text — shaped generations of families across racial and economic lines.

Understanding why this happened, and what it set in motion, helps us see how American laws weren’t just responding to society — they were actively creating it.

The law read: “All children borne in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother.”

To modern eyes, that might not look explosive. But it was a complete reversal of the legal norms colonists brought from Europe.

Up to that moment:

But plantation owners had a problem. The system of slavery they were expanding depended on controlling labor — and controlling people’s children. Under paternal lineage, the children of white men and enslaved women would legally be free, which threatened the entire economic model. So the lawmakers changed the rule.

By tying a child’s status to the mother, the colony ensured three things:

This wasn’t just a family law update. It was the foundation of a massive economic engine.

They bore the heaviest burden. This law turned their bodies into an economic resource. Children they carried were automatically enslaved, regardless of the father. The emotional and generational toll is beyond measure.

Many settlers didn’t benefit from the plantation economy. But the new law created a racial boundary that gave poor whites a legal and social distinction from enslaved people — even when their material conditions were similar. That wedge prevented multiracial worker alliances for generations.

Colonists applied similar lineage laws to justify enslavement of Indigenous people in certain regions. The same logic — “status follows the mother” — became a way to control and classify Indigenous labor.

Irish, Scottish, and other European immigrants inherited a legal world where racial hierarchy was baked in. Their gradual inclusion in the category of “white” depended on these early lineage laws.

The ramifications of the 1662 statute rippled outward through property laws, marriage laws, adoption policies, and how families were tracked in government records. It influenced policing, census categories, and even modern debates about citizenship.

When people say slavery shaped America, this is one of the clearest examples of how deeply and intentionally that shaping occurred.

Even though the law itself is long gone, its fingerprint is still visible:

Lineage laws weren’t just words on paper. They sculpted the social landscape.

Understanding this law isn’t about looking backward for the sake of it. It’s about seeing how one policy can:

And importantly:

It shows how powerful it can be when laws redefine who belongs, who counts, and who can pass opportunity on to the next generation.

Those patterns didn’t stay in the 1600s. They shaped the world we all inherited.

Library of Congress — Early Virginia Statutes

https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trr043.html

National Archives — Foundations of Colonial Law

https://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records

Virginia Museum of History — Laws on Status and Lineage

https://virginiahistory.org/

Smithsonian — The Legal History of Slavery and Family

https://nmaahc.si.edu/

UNC Digital Collections — Colonial Family Records

https://dc.lib.unc.edu/